Could Joseph have hidden material in his hat to draw upon during the dictation process?

Foreword

The most compelling model for the creation of the Book of Mormon is that Joseph Smith primarily composed the book orally. Still, the following is an interesting counter-theory (or perhaps supplement) to that model.

Introduction

Two main data points converge to suggest that a pre-written text of some kind was used for the dictation of the Book of Mormon.

- The Book of Mormon text demonstrates a high level of consistency and complexity (also see the work of Royal Skousen).

-

The dictation of the manuscript that became the Book of Mormon as we have it today appears to have occurred during relatively few working days (perhaps around 65). Welch writes:

nearly all the 590 pages printed in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon were translated, dictated, and written within an extremely short and intensely busy period of time, from April 7 to the last week of June 1829. Virtually no excess time existed during those three months for Joseph Smith to plan, to ponder about, to research, to hunt for sources, to organize data, to draft, to revise, or to polish the pages of the original manuscript of this book. Although Joseph became aware of and began contemplating this assignment in September 1823, and while he translated the 116 pages containing the book of Lehi from April 12, 1828, to June 14, 1828, which were sadly lost that summer, once Joseph and Oliver set to work on April 7, 1829, the pages of the Book of Mormon flowed forth in rapid succession. The text of the Book of Mormon was dictated one time through, essentially in final form. This was done despite significant interruptions and distractions. Such a feat, in and of itself, constitutes a considerable achievement, given the length, quality, and complexity of the Book of Mormon alone.

LDS leaders have argued that the relatively short translation time period coupled with the complexity of the text (including doctrinal richness) is indicative of divine intervention (e.g. here and here).

Other data points also support the idea of a pre-written manuscript but simultaneously cast doubt on the book as an ancient record. For instance, LDS scholars and critics alike have also noticed that the the Book of Mormon contains an enormous amount of material which closely parallels existing texts from the early 1800s. While most historians view Joseph as author/dictator of the text, some lesser-known theories rely on a manuscript prepared in advance (e.g. Criddle, Hancock, Trebas). In addition, the dictated manuscript seems to reference biblical features that reflect the understanding of the time and were not likely to have existed as dictated in any ancient sources:

-

The inclusion of Deutero-Isaiah assumes that Joseph referenced the relevant KJV chapters and dictated them to his scribe. Grant Hardy explains:

Latter-day Saints sometimes brush [deutero-Isaiah] criticism aside, asserting that such interpretations are simply the work of academics who do not believe in prophecy, but this is clearly an inadequate (and inaccurate) response to a significant body of detailed historical and literary analysis. … Recent Isaiah scholarship has moved away from the strict differentiation of the work of First and Second Isaiah (though still holding to the idea of multiple authorship) in favor of seeing the book of Isaiah as the product of several centuries of intensive redaction and accretion. In other words, even Isaiah 2–14 would have looked very different in Nephi’s time than it did four hundred years later at the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, when it was quite similar to what we have today. (emphasis added)

-

There are at least a handful of KJV translation errors which are included in the Book of Mormon (i.e., the original Hebrew would not have been understood that way and so the translation reflects copying from the KJV Bible rather than a fresh translation of an ancient source). It seems highly unlikely that JS would have transmitted or understood these verses in the way that he did (remember, the original Hebrew does not convey the message encapsulated in the KJV translation) unless he were referring to notes, somehow.

-

The Book of Mormon copies a few verses verbatim from Mark 16 but these verse are highly likely to be a later invention. In other words, we have Nephite scribes recording Jesus saying words found in the New Testament that Joseph Smith had access to, but these words were almost certainly not transmitted by Jesus in the manner recorded in the New Testament.

There are good reasons, then, to suggest that no individual (divine aid or not) could have impromptu woven together so many ideas and blocks of text regardless of any prodigious story-telling and doctrinal-generating abilities they may have possessed.

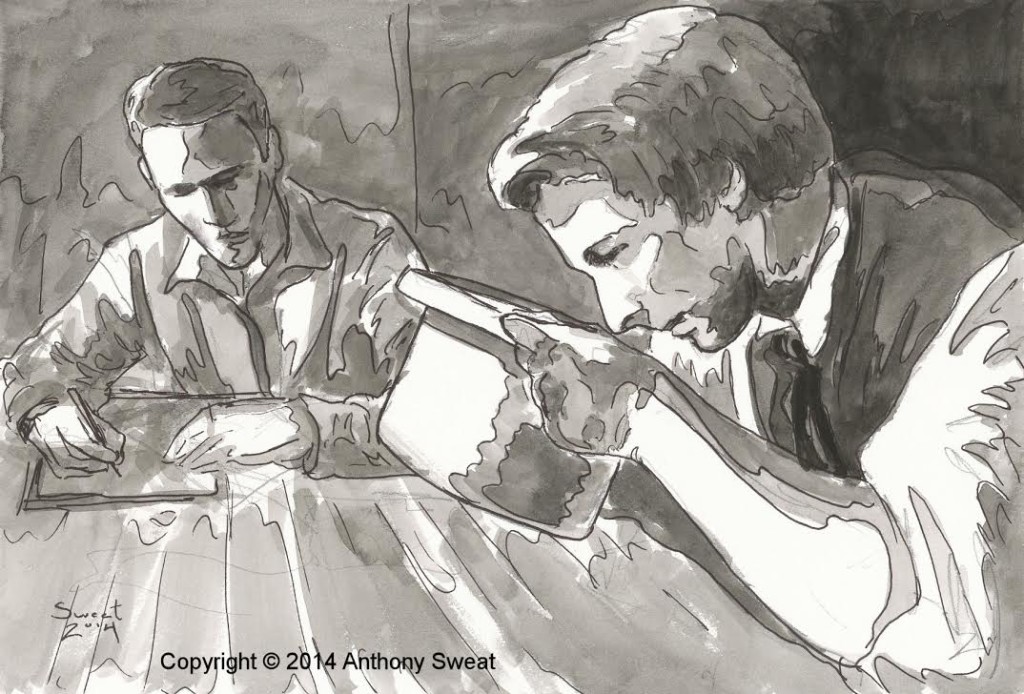

The current orthodox/apologetic model for the translation of the Book of Mormon primarily involves Joseph Smith placing his seer stone in his hat and then dictating the manuscript to a scribe. Eyewitness accounts of the dictation process do not indicate that Smith was referring to a manuscript or other notes, and Emma’s account explicitly rules out the use of a manuscript. The LDS believer is quick to conclude from these accounts that a divine transmission process is the only viable explanation. For the naturalist, the alignment of all these facts presents an interesting problem: besides invoking a conspiracy on a grand scale (i.e., everyone was, or at least all key players were, in on it), what possible method(s) could allow Smith access to a manuscript or manuscript sections without detection of his scribes or passive observers (so, assuming that dictation proceeded as many witnesses indicated)?

This document explores the possibility that Joseph hid material in his hat which he was able to draw upon during the dictation process.

The Model Requirements

The model whereby Joseph hides material in his hat to aid him during the dictation process depends upon six main elements in order to be viable. If any one of these were found to not be viable, the model may be considered falsified. If all six of these elements can be demonstrated viable, then the model as a whole may also be viewed as viable, it would seem.

-

Close examination discouraged

Observers and scribes would need to be discouraged from examining the hat too closely both while Joseph was translating and if he merely left the hat on the table in order to leave the room (otherwise they might observe the material Joseph was using).

Joseph and Oliver referred to translation with the Urim and Thummim but this is contradicted by other accounts (for instance, Emma notes that after the loss of the 116 pages, Joseph began translating with the seer stone). Regardless of his motivation for avoiding reference to the seer stone and hat, Oliver’s 1841 interview with Josiah Jones stressed the need to not look into the translation apparatus:

I then asked him [Cowdery] if he had ever looked through the stones to see what he could see in them; his reply was that he was not permitted to look into them. I asked him who debarred him from looking into them; he remained sometime in silence, then said that he had so much confidence in his friend Smith, who told him that he must not look into them, that he did not presume to do so lest he should tempt God and be struck dead. (emphasis added)

Although Cowdery did attempt to translate (with the hat and seer stone?), it would have been trivial for Smith to simply not deposit a fragment before Cowdery’s attempt.

Although the early part of the translation process may not have proceeded with the seer stone in a hat, a similar level of concealment is indicated here, too. John A. Clark spoke with Martin Harris and conveyed:

Although in the same room, a thick curtain or blanket was suspended between them, and Smith concealed behind the blanket, pretended to look through his spectacles, or transparent stones, and would then write down or repeat what he saw, which, when repeated aloud, was written down by Harris, who sat on the other side of the suspended blanket. Harris was told that it would arouse the most terrible divine displeasure, if he should attempt to draw near the sacred chest, or look at Smith while engaged in the work of decyphering the mysterious characters. (emphasis added)

-

A deep hat

The hat would need to be deep enough to hide a manuscript from casual observation.

- David Whitmer described the hat as “a deep hat.”

- Pat Chiu apparently determined that Joseph owned a beaver-skin hat with a “top hat” profile. These hats are typically fairly deep—deep enough that a casual observer from the side would not be able to detect a paper or cardstock fragment in the bottom.

-

A wide hat

The hat would need to be wide enough to hold a significant amount of material.

How large was Joseph’s hat? As noted, Pat Chiu apparently determined that Joseph owned a beaver-skin hat with a “top hat” profile, and these have a large diameter top (or bottom when inverted). To emphasize the size of these hats, I note that Abraham Lincoln kept important letters inside his stovepipe hat,(Benjamin P. Thomas (26 September 2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Biography. SIU Press. pp. 39. ISBN 978-0-8093-2887-1) which is roughly the same size as the kind of top hat Joseph was likely to have worn (compare romantic era hats with Lincoln’s hat)

In an interview, David Whitmer communicated that “an oblong piece of parchment” appeared to Joseph. If the parchment were actual instead of visionary, how much text could it have held?

- 93.5 square inches on a sheet of letter paper

- A hat 6 to 8 inches in diameter would have yielded between 28 and 50 square inches, or between 1/3 to 1/2 the area of a standard sheet of paper.

It seems reasonable, then, to suggest that a single hat-sized fragment could have held somewhere between 100 and 150 words. And, if pictographs or some form of shorthand were used, significantly more content could have been encoded on a given manuscript fragment.

-

Time to understand and embellish manuscript notes

Joseph would need time to decipher what was on the manuscript and/or extrapolate/embellish some of the material.

As discussed below, Joseph probably needed to dictate about 25 (modern) verses per session. If a session lasts one or two hours, then this seems a very reasonable rate to allow for reflection, recall, and embellishment.

-

An opportunity to swap out manuscript notes

Material would need to be swapped into and out of the hat at least a few times daily.

First, we know that Joseph took breaks while working on the JST, and Emma’s account of his translation implies that he took breaks (“when he stopped for any purpose at any time”). Translation breaks provide a reasonable opportunity to swap out material.

How could Joseph have swapped out a manuscript fragment without passive observers noticing?

The seer stone itself may have provided the needed misdirection. Joseph carried a stone on his person, which means that he had a potential reason to reach into his hat at the beginning of each session to deposit the stone and at the end of each session to retrieve the stone. During this action, a fragment could have been deposited and then retrieved along with the rock. Perhaps the fragment was merely placed inside Smith’s shirt/jacket sleeve (similar to the card in sleeve trick). Regardless of the exact mechanics, depositing and retrieving the seer stone provides one potential source of misdirection to enable a manuscript swap.

-

Some light to illuminate the manuscript

Light would need to be able to enter the hat in some manner or frequency1 in order for Joseph to be able to view the material on the manuscript.

Martin Harris once described the hat Joseph used for finding lost objects as being “white”2 and some informal experimentation with a similar white hat from the era demonstrated that text could be viewed within it, in part because the material was somewhat translucent.3

Doing the math

Given what we know about the translation process, what would a typical Smith/Cowdery dictation session have looked like under this model?

[Note, the following uses modern page numbers and verse demarcations for an analysis easier to grasp for the modern reader. So, the following assumes the content of the modern BoM is similar in length to the content of the original manuscript.]

- 531 pages and 273,725 words in the modern Book of Mormon, so roughly 515 words per page.

- Assume 65 working days, with 4 sessions per day (each session would have provided him the opportunity to swap out material, as explained above) for a total of 260 dictation sessions. This means that roughly two modern pages, or 1000 words, needed to be dictated per session.

- As noted above, a single hat-sized fragment could have held somewhere between 100 and 150 words.

- There are 6604 verses in the Book of Mormon, so Smith needed to dictate approximately 25 verses, or 1000 words, per session.

Assuming the above, Joseph had space on his hidden parchment for roughly 4 to 6 English written words per verse, or 1 hidden-manuscript word per 6–10 dictated manuscript words.

This compression ratio (4–6 hidden manuscript words per modern verse of about 40 words) corresponds well with the compression ratio we see between individual characters and the associated verbiage found in the Book of Abraham in the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language where, on average, we see between 10 and 40 words associated with each Egyptian character. (Please consider Vogel’s arguments demonstrating that the GAEL indeed represents the dictation event of the Book of Abraham contrary to what some LDS scholars have argued.)

In other words, under the naturalist model, Joseph Smith seems capable of embellishing scripture associated with representations that could have easily been contained on a fragment that would have fit neatly inside his hat.

Perhaps this would have been more difficult to do with extended sections of Isaiah, but remember that only a subset of the Isaiah verses are word for word. In addition, Joseph would only need to request more breaks and shorter sessions in order to increase the amount of text he could refer to for a given section in the Book of Mormon.

Finally, the Quran has about the same number of verses in it as the Book of Mormon and the Quran can be memorized in between 8 months to 1.5 years. So, given that the dictation process was spread out over time, it is also seems possible that Joseph could commit verses to short term memory (or become very familiar with them) between dictation sessions (particularly if aided by a fragment).

Other data points explained by this model

The following find a good explanation with the manuscript in a hat theory. This theory may help to explain why:

-

Joseph Smith deflected discussion on the mechanism of translation

Explaining the particulars about using a stone in a hat (besides drawing attention to the occult nature of using seer-stones) might have also suggested that material was being hid in the hat for Joseph to refer to.

For instance, Hyrum directed interest in how the Book of Mormon was translated to Joseph Smith (“he thought best that the information of the coming forth of the book of Mormon be related by Joseph himself”), and Joseph responded:

it was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the book of Mormon, & also said that it was not expedient for him to relate these things &c” (Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 23). (from JF McConkie)

-

Oliver Cowdery could not translate using the seer stone

Joseph Fielding Smith and Craig Ostler explain:

if the process of translation was simply a matter of reading from a seer stone in a hat, surely Oliver Cowdery could do that as well, if not better, than Joseph Smith. After all, Oliver was a schoolteacher. How then do we account for Oliver’s inability to translate?

And, note that after Cowdery fails in his translation, the next passages translated by Joseph Smith in the Book of Mormon, in what “seems more than coincidence”, immediately lend plausibility to the idea that only certain people have the gift to be able to “look, and translate … records … of ancient date; and it is a gift from God”:

It seems more than coincidence that one of the first things translated by Joseph Smith after Oliver Cowdery became his scribe was the story of King Limhi asking Ammon if he could translate the records in his possession. (see JF McConkie)

-

Joseph was able to pick up exactly where he had left off

Emma recounted:

When he stopped for any purpose at any time he would, when he commenced again, begin where he left off without any hesitation

If he were swapping out fragments between sessions, then there would have been no question as to where he should start because the starting location would correspond with the beginning of his manuscript fragment.

-

Joseph was occasionally surprised at details in the material he was dictating:

Emma recounted:

one time while he was translating he stopped suddenly, pale as a sheet, and said, “Emma, did Jerusalem have walls around it?” When I answered “Yes,” he replied “Oh! I was afraid I had been deceived.”

Joseph’s surprise by the material he was dictating makes sense if he were working from existing notes.

-

The plates themselves were never used

Even though the plates contained the characters apparently displayed on the seer stone, the plates themselves were not ever needed and were never actually referred to.

-

An unexplained break in translation was needed as described in D&C 5:30

D&C 5:30 and 5:31 are adamant that Joseph stop translating “for a season”:

when thou hast translated a few more pages thou shalt stop for a season, even until I command thee again; then thou mayest translate again. And except thou do this, behold, thou shalt have no more gift, and I will take away the things which I have entrusted with thee.

This may correspond to the need of those preparing the manuscript to finish their work related to the lost 116 pages (or perhaps to stay ahead of the translation process generally).

-

Isaiah is transmitted in essence but often not with exactness.

Grant Hardy notes:

It is possible that when Joseph Smith felt the need to quote Isaiah, he opened his Bible and read the chapters aloud, making whatever changes he deemed necessary. Yet this explanation does not account for the irregularities that we see—some of the alterations increase parallelism or make Isaiah easier to understand, while others fragment the text or make it more obscure.

The manuscript likely couldn’t hold the entirety of the Isaiah text, so Joseph would have needed to fill in some of the verbiage from memory, and this could help to account for a close—but not exact—transmission.

-

Older English constructs appear in the book

If the book were based on a manuscript, then the kinds of words contained in it may have been pulled more easily from other, earlier sources during the manuscript’s initial creation. It seems less likely that Smith would use a variety of out-of-date verbiage of his own accord if he were generating the book on the fly.

-

Theology reminiscent of Sidney Rigdon appears in the book

Although scant evidence of a chronological nature implicates Rigdon in the translation process of the Book of Mormon (which is expected if his participation was meant to be obscured by the participants), Rigdon-esque theology appears throughout the Book of Mormon. The manuscript-in-a-hat theory gives more room for Rigdon to have participated in the creation of an initial, or perhaps, ongoing manuscript. See Criddle’s work on Rigdon’s possible influence on the Book of Mormon.

-

A white, translucent hat is the simplest explanation and a white hat is consistent with available evidence on the color of Joseph’s hat; however, even if the hat were not light/translucent, it is still possible that enough light could be used to view material hidden within it:

- Even though Emma, William Smith, and David Whitmer variously described Joseph pressing his face into the hat to exclude all light, David Whitmer also once said that Joseph Smith was merely “placing his face close to [a deep hat]” (emphasis added). So, although the weight of the witness testimony favors Joseph putting his face up to the hat, one description allows for some space.

- Presumably, Joseph would pull his head away from the hat in order to dictate the words—it is difficult to imagine that his speech would be clear enough were he to dictate into the hat. So, each verbal communication afforded a chance for light to enter the hat and for him to gaze down into the hat before sealing his face to it.

- It is very difficult to perfectly seal one’s face to the mouth of a circular hat. Furthermore, Joseph’s face was somewhat elongated, making a perfect seal around a circular hat likely something difficult to achieve. Regardless of the tightness of the seal itself, simply tilting one’s head slightly can allow streams of light to enter from various angles.

- Most of the top hats of the era had ribbons running around them. Perhaps a slit or two could have been prepared beneath the ribbon. Then, when translation was to proceed, the ribbon could be slid slightly up or down while fingers could simultaneously obscure the slit from observers. The slit could allow in light.

- The seams around the top of the hat (so the bottom of the hat during translation) may have been somewhat loose. The rock could have helped to open the seams to allow in some light.

-

In an interview in 1859, Martin Harris described the process Joseph used for finding lost objects:”He took [the stone] [out] and placed it in his hat–the old white hat–and placed his face in his hat.” ↩

-

Bill Reel apparently has in his possession a white top hat like Jopseh might have used. RFM remarked that the material was fairly translucent, allowing a fair amount of light through the white material. ↩